+91-9958 726825

An unusual case of co-occurrence of Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Mog-Antibody Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder

|

Background: “Guillain-Barré Syndrome” (GBS) is a rapid-onset, immune-related neuropathy affecting the peripheral nervous system. It frequently occurs after an infectious disease and presents with symmetrical weakness and sensory deficits that progress upward. In contrast, “Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder” (NMOSD) is a central demyelinating disorder typically linked with aquaporin-4 (AQP4) or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies, mainly affecting the optic nerves and spinal cord.

Case Presentation: We present a case of a 26-year-old woman experiencing worsening weakness, involvement of cranial nerves, and respiratory distress. Neuroimaging indicated medullary hyperintensities that suggest central demyelination, and serological tests confirmed the presence of MOG antibodies, aligning with a diagnosis of NMOSD. At the same time, symptoms consistent with acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy supported the diagnosis of GBS. The patient underwent a tracheostomy, received enteral nutrition, was treated with antibiotics for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and received supportive care in the ICU. She demonstrated gradual improvement without the use of immunosuppressive treatment. Conclusion: This distinctive situation highlights the significance of promptly identifying overlapping autoimmune disorders. Swift diagnostic assessment facilitated customized treatment, leading to a positive recovery. |

|

“Guillain-Barré Syndrome” (GBS) is an uncommon autoimmune neuropathy that can be life-threatening, primarily affecting the peripheral nervous system (PNS).[1] It is typically marked by quickly progressing, symmetrical weakness in the limbs, loss of reflexes, and varying degrees of sensory impairment. Many instances occur after a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection, which is thought to trigger an abnormal immune response that harms peripheral myelin.

In contrast, “Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder” (NMOSD) is a demyelinating disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS), including the optic nerves, spinal cord, and brainstem. It is highly associated with antibodies targeting aquaporin-4 (AQP4); however, certain patients, especially those with lesions in the brainstem or cerebral cortex, may also test positive for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies. [2][3] [4]. Autoantibodies play a crucial role in the mechanisms of various diseases and have become essential for diagnostic classification. While both “Guillain-Barré Syndrome” (GBS) and “Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder” (NMOSD) are autoimmune demyelinating disorders, they impact different regions of the nervous system—the peripheral nervous system in GBS and the central nervous system in NMOSD—and are characterized by distinct immune processes and clinical trajectories. The simultaneous development of both conditions in a single patient is extremely uncommon, posing challenges for diagnosis and management. In this report, we describe a 26-year-old female patient who initially exhibited typical symptoms of GBS, such as flaccid quadriparesis and cranial nerve impairment. Later imaging results showed involvement of the medulla, and the presence of positive MOG antibodies confirmed a secondary diagnosis of NMOSD.The fact that this patient had both diseases necessitated careful interpretation of the clinical presentation, imaging results, and serologic data, and underscores the necessity for increased clinical suspicion in the setting of symptomatology that transcends the usual anatomical borders of either condition[5] . |

|

Case Report

A 26-year-old female patient had come on 30th November 2022 with progressive weakness and numbness of all four limbs, giddiness, difficulty in speaking, difficulty in swallowing, and fatigue. Her husband reported that she had also developed a feeling of suffocation and decreased appetite for several weeks. She had recently had pneumonia two weeks ago and had gastrointestinal symptoms with vomiting. |

|

Results: Clinical and Diagnostic Findings

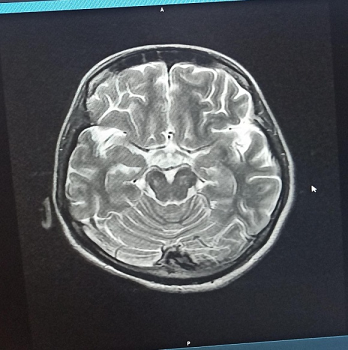

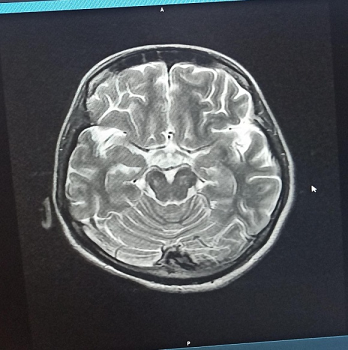

Radiological Findings:  Figure 1 : Brain MRI (T2-weighted axial view) showing hyperintensities in the posterior medulla, suggestive of NMOSD involvement.

Figure 2 : MRI spine showing Schmorl’s node at L3 with disc bulges at L4-L5 and L5-S1 indenting the thecal sac and causing bilateral foraminal compromise.

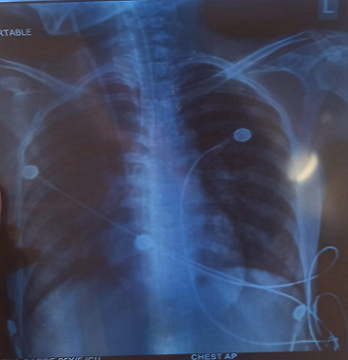

Figure 3 : Chest X-ray (PA view) showing bilateral patchy heterogeneous opacities, most prominent in mid and lower lung zones, suggestive of possible consolidation.

Medical Laboratory Findings:

Table 1 : Serial blood parameters, including haemoglobin, blood urea, and uric acid

Treatment |

|

This patient exhibited progressive weakness, bulbar symptoms, and areflexia, suggesting a diagnosis of “Guillain-Barré Syndrome” (GBS), most indicative of the acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) variant. Typical for severe GBS cases are symmetrical paralysis, cranial nerve involvement, and autonomic issues such as arrhythmias and hypotension [11].

Nevertheless, the disease’s progression extended beyond peripheral manifestations. An MRI of the brain revealed T2 hyperintense areas in the posterior medulla—atypical for GBS—and serological analysis confirmed MOG antibody positivity, identifying “Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder” (NMOSD) as a concurrent condition. The combination of central and peripheral demyelination, although rare, has been increasingly acknowledged, particularly among cases positive for MOG antibodies [12–15]. MOG-associated NMOSD commonly presents with optic neuritis or transverse myelitis, but brainstem lesions, particularly in the medulla, have also been documented. Symptoms like dysphagia, vertigo, and hiccups indicate such involvement, corresponding with this patient’s clinical presentation. Therefore, it was crucial to determine whether the decline was attributable to peripheral GBS or central NMOSD. The patient’s situation was further complicated by severe illness and a secondary hospital-acquired infection. A chest X-ray indicated bilateral opacities, and cultures identified multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, a pathogen known for its resistance and association with ICU settings [12][16][17]. Effectively addressing these infections necessitates careful antibiotic selection and stringent infection control measures. Remarkably, despite the simultaneous pathologies and infection, the patient demonstrated improvement with supportive care alone—ventilatory support, nutrition, physiotherapy, and appropriate antibiotics. She did not need immunotherapy options such as IVIG, plasmapheresis, or corticosteroids, which are generally considered for GBS and NMOSD. This outcome emphasizes that tailored care, based on clinical stability and gradual improvement, can, in certain cases, be sufficient without aggressive treatment[18][19]. From a broader perspective, this case highlights that central and peripheral demyelinating conditions can coexist. Disorders associated with MOG may affect both areas, increasing the need for awareness of atypical manifestations. Furthermore, it underscores the significance of multidisciplinary cooperation—neurology, critical care, infectious disease, physiotherapy, and nursing teams all played vital roles in the recovery process.[20-23] In summary, this report emphasizes the importance of promptly identifying overlapping neuroimmunological disorders, conducting thorough diagnostic assessments, and exercising careful clinical judgment in customizing treatment. |

|

This case demonstrates the complexity of diagnosing and managing overlapping autoimmune neurological syndromes, particularly when GBS coexists with MOG-antibody-positive NMOSD. Such cases remain rare and are often under-recognized, which can delay appropriate intervention. In this patient, early recognition of both central and peripheral involvement enabled a focused diagnostic approach, while careful clinical judgment prevented overtreatment. Despite not receiving aggressive immunotherapy, the patient improved steadily, emphasizing that supportive care — when timely and well-coordinated — can be just as critical as pharmacological treatment in certain clinical contexts.

The lessons from this case are several. First, never rule out central involvement in a presumed peripheral neuropathy, especially when atypical symptoms or MRI changes are present. Second, MOG antibody testing should be considered when brainstem signs or imaging abnormalities accompany peripheral demyelinating features. Third, the role of hospital-acquired infections must not be underestimated, particularly in patients requiring intubation and ICU stay. Lastly, this case is a reminder that medicine is both an art and a science — knowing when to treat aggressively and when to allow the body to recover with support is a nuanced, experience-driven decision. In conclusion, the co-occurrence of GBS and NMOSD, though unusual, can be successfully managed with a multidisciplinary, evidence-informed approach. This case serves as a meaningful reference for future clinical situations involving dual pathology and emphasizes the growing need for integrated neuroimmunological diagnostics in acute neurology settings. |

|

|

Dhwani Bariya, Dr. Nivedita Priya (2025), An unusual case of co-occurrence of Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Mog-Antibody Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. International Research & Advancement in Microbiology and Biotechnology, 1(1) .