+91-9958 726825

Advances in instrumentation and techniques in stem cells research: A Comprehensive Literature Review

|

Stem-cell research is an essential basis of modern biomedical research, given the unique and remarkable properties of stem cells. This literature review assesses the currently available knowledge of stem cells, while also acknowledging the continuously changing landscape of advanced technologies and instrumentation techniques in the discovery of stem cell structure and function. It also provides a thorough appraisal of the complexity of stem cell culture, which includes protocols and culturing conditions that maintain pluripotency and cell viability.

The review provides a snapshot of modern genetic approaches, neural CRISPR/Cas9, used with conventional transfection and transduction approaches, to make specific cell phenotypes. Advances in imaging, single cell approaches, and live cell tracking also provide a close-up look at stem cell behaviours whereas biomaterials and scaffolds supports its growth and engineering. Clinical applications of stem cells are also noted through current trials related to disease modelling and regenerative therapies. Importantly, ethical, regulatory and technical issues including reproducibility and scaling issues were carefully considered. This narrative provides information and direction to both experienced and inexperienced researchers, embryologists, clinicians and trainees, by highlighting progress and acknowledging issues within the rapidly-evolving world of stem cell research. |

|

Background and Importance

Their capacity for sustained proliferation and their potential to develop into specialized somatic cells have positioned them as a major area of focus in contemporary biomedical research. They are distinguished by their remarkable capacity to give rise to multiple specialized cell lineages, making them indispensable to advances in basic science as well as translational biomedical research. The main types

arise from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst stage of the embryo and are pluripotent As seen in Figure 1 Embryonic stem cells arise from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst stage of the embryo and can become almost all cells in the body. However, pluripotent ESCs raise ethical concerns and possess the capacity to form tetramic formations when used in therapeutic functions. Distributed among various tissues such as bone marrow, liver, and brain, adult stem cells exhibit multipotency, allowing them to contribute significantly to the ongoing maintenance and regeneration of the tissues in which they reside (2). Today, adult stem cells have fewer ethical concerns and are used more frequently in therapeutics(3). “Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are derived by converting mature somatic cells into a pluripotent state through the ectopic activation of a defined combination of transcription factors, and combine the benefit of ESCs type pluripotency with the reduced ethical issues of ASCs (4). iPSCs carry the potential for personalized clinical applications, in addition to disease modelling and providing a powerful platform for Regeneration-focused therapeutic strategies. The importance of stem cells in biomedical approaches aimed at tissue repair and renewal can hardly be exaggerated. They offer a possible solution to degenerative diseases and trauma which fall short of current conventional medical therapies. For example, Ongoing research endeavors directed toward the development of stem cell–based therapeutic approaches for Parkinson and diabetes disease (5). In addition, stem cell–based models provide powerful tools for dissecting disease pathophysiology and supporting the development and evaluation of novel therapeutic agents. Advances in stem cell–derived organoid technology have opened new avenues for studying organogenesis, disease dynamics, and treatment responsiveness within highly controlled model systems. (6).  Figure 1 : Illustration of Stem Cell Types |

|

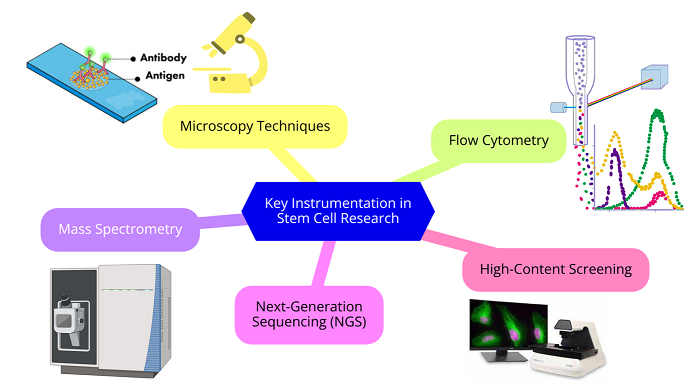

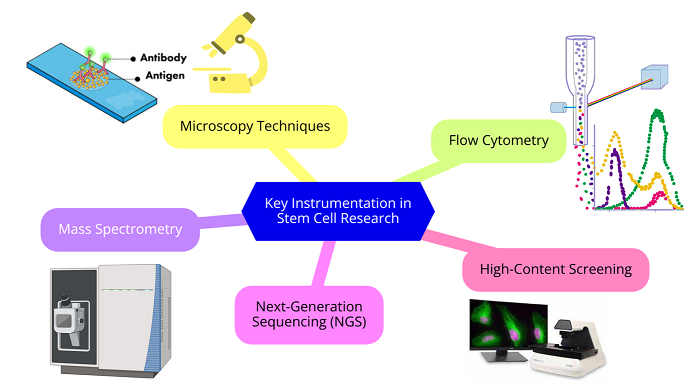

This article will present an in-depth description of the instrumentation and important procedures involved with stem cell science and applications. We chose to concentrate our efforts on summarizing and reviewing the instrumental developments that have ushered the science of stem cells into the current era, with an emphasis on more accurate study of properties and possibilities of the science. This article considers the gamut of methods and techniques in stem cell research from the basic concepts and protocols of stem cell culture to advanced methods in genetic engineering and microscopy. The article discusses major instruments (e.g., microscopy, flow cytometry, mass spectrometry, and next-generation sequencing (NGS)) needed to characterize the stem cell populations, deciphering the molecular signatures, modulating their functions in vitro, and tracking cellular behavior in vivo. Notably, this review includes novel developments in stem cell research, including CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, high-content screening as a platform for drug discovery, and bioprinting in tissue engineering. Every topic discusses their ramifications, advantages, and their limitations, as well as the basics of the method itself. With this review, we provide an extensive outline of the tools and techniques of the field, as we hope to add to the developing knowledge base of researchers to enhance their ability to leverage the use of these technologies for their research. It showcases emerging trends and current advancements, whilst suggesting ways these discoveries may impact the future of stem cell research. The primary purpose is to marry emerging technology with novel applications and to familiarize readers with the state of the art and future directions in stem cell science's instrumentation and technique.

|

|

Stem Cell Biology: Basic Concepts

Properties and Characteristics Stem cells demonstrate a unique capacity to sustain continuous self-renewing activity and to differentiate across diverse specialized cellular lineages, making them highly valuable in both fundamental biological investigation and clinical practice. In this self-renewal process, stem cells undergo division to produce identical progeny that retain an undifferentiated state, thereby ensuring a sustained pool of stem cells. This self-renewal process includes “Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog” signalling pathways, that act in a complex manner to ensure its characterstics are kept in a distinct balance (6). The differentiation process is where the stem cell is progressively converted through a series of regulated changes into a specialized cell type. This process is influenced by intrinsic and/or extrinsic factors; intrinsic factors including patterns of gene activity and epigenetic regulation, and extrinsic factors including cues derived from the surrounding microenvironment. During cellular differentiation, the stem cells progressively lose their self-renewal capability, while simultaneously gaining the ability to carry out specialized functions. Stem Cell Niches and Microenvironments Stem cell behavior is largely affected by the niches in which they exist. These niches contain the specialized microenvironments with physical and biochemical signals required to maintain stem cell properties and regulate their fate decisions, which can be seen in Table 1. Whereas the cellular microenvironment associated with a stem cell niche is shaped through the interactions between distinct cell types present within the niche, which can provide factors through direct contact with the cells as well as para-crine signalling. Moreover, extracellular matrix (ECM) elements including collagen fibres, lamina, as well as fibronectin provide mechanical support and are devising roles in signalling via integrin receptors and other ECM-binding proteins. Hypoxia, or a low oxygen condition, is another important aspect in some stem cell niches which regulates stem cell function through hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) and supports a self-renewal state while inhibiting differentiation (13). Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are thought to exploit normal stem cell niches enhancing the microenvironment to support the growth of tumors and resistance to therapy (14). Therefore, knowledge of the complexities of stem cell niches and regulatory elements is essential for developing strategies to manipulate stem cell behavior for therapeutic manipulation as well as to devise interventions to regress CSCs in cancer therapy.

Table 1 : Summary of Key Concepts in Stem Cell Properties, Characteristics, and Niches

Key Instrumentation and techniques in Stem Cell Research (illustrated in Figure 2)  Figure 2 : Key Instrumentation in Stem Cell Research

Table 2 : Key Instrumentation

Stem Cell Culture & Maintenance

Table 3 : Techniques for Stem Cell Culture and Maintenance

Differentiation Techniques

Table 4 : Differentiation Techniques

Genetic Engineering of Stem Cells

Table 5 : Advanced Imaging and Analysis Techniques in Stem Cell Research

Biomaterials and Scaffolds |

|

Technical Challenges

The area of stem cell research, although promising, has a number of technical hurdles that hinder its advancement and utilization. One of the biggest challenges is its reproducibility. Reproducibility is essential to confirm research results and to transfer them into clinic trials. Yet, heterogeneity in stem cell culture conditions, differentiation protocols, and experimental methodologies can result in variable results. Several factors including the origin of stem cells, reagent-to-batch variations, and the variations in laboratory practices lead to this reproducibility crisis (78). Standardizing procedures and having strict quality control practices are critical to resolve these challenges and increase the overall robustness of stem cell research. Scalability is another key challenge, especially in preparing the stem cells and their derivatives for therapeutic use. Scaling up the production of large amounts of stem cells that retain their pluripotency and differentiation ability involves highly advanced bioreactor systems with highly optimized culture conditions (79). In addition, scale-up production needs to be ensured consistently and with adherence to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards to satisfy requirements for clinical use. These issues of scalability need to be addressed for stem cell-based treatments to gain broad acceptance. The absence of standards that are commonly acceptable across cell characterization, differentiation protocols, and functional assays is a significant impediment to comparability of results between and among studies and laboratories (80). Biological Limitations Stem cell research also faces some biological constraints influencing its clinical translation. One of them is genetic stability since prolonged culture and stem cell manipulation may provoke genetic and epigenetic changes. Such changes may influence the efficacy as well as the stability of stem cell-based treatments. For example, the imposition of chromosomal abnormalities during in vitro expansion may accelerate tumorigenicity (81). Maintenance of genetic stability through monitoring and quality control is necessary to counteract such risks. These cells are able to produce teratomas, benign growths composed of tissues originating from all three germ layers, when they are implanted into hosts (82). In most instances, the recipient’s immune system can detect implanted cells as foreign and mount an immune reaction, resulting in rejection. Even autologous iPSCs can also trigger immune responses because of immunogenic changes incurred during reprogramming (83). Establishing critical strategies to impose immune tolerance, including gene editing to alter immunogenic epitopes or co-administration of immunosuppressive drugs, is a critical aspect for improving the therapeutic treatments. |

|

The science of stem cells stands ready to transform biology as well as clinical medicine, holding unprecedented prospects for explaining human development, disease modelling, and innovative therapeutic strategies.

This review has delineated the specific properties and functions across diverse stem cell populations to discuss their potential roles in curing complex diseases. The recognition of stem cells as a foundational component in biomedical research represents a major breakthrough. The specific abilities for sustained self-renewal and lineage-specific differentiation have provided a strong paradigm for investigating developmental biology and regenerative medicine. Advances in novel techniques, instrumentation, culture methods, differentiation protocols, gene manipulation, and biomaterials have all contributed to advance the field. In this thorough coverage of stem cell science, we have touched on the basic concept, novel techniques, and major key challenges that will define the future of this exciting field. Although the major challenges persist—ranging from technical reproducibility to clinical translation, the emergent innovations continue to enhance stem cell science capabilities. Utilizing the sustained interdisciplinary collaboration and ethical stewardship, stem cell research holds the capacity to reshape precision medicine and redefine the trajectory of future healthcare. |

|

|

Dr. Sunil Kumar, Dr. Arti Thakur (2025), Advances in instrumentation and techniques in stem cells research: A Comprehensive Literature Review . International Research & Advancement in Microbiology and Biotechnology, 1(1) .